Since it first debuted in mid 2007, Mad Men has grown to become one of the most popular and decorated shows on television. Set in 1960’s Manhattan, the series follows Don Draper, a fictional advertising executive, as he navigates the high stakes world of the Madison Avenue advertising industry. Taking place during what was a turning point for both the nation and the advertising industry, Mad Men attempts to take viewers into the world of the men whose work shaped an era of pop culture communication.

Now while Mad Men has received numerous awards for the performances of its cast and quality of its writing, it is it’s perceived authenticity that has garnered the show it’s highest praise. From the visual design of sets and the meticulous selection of the wardrobe donned by the cast, to the portrayal of such overarching themes as sexism, alcoholism and office promiscuity, Mad Men has prided itself on attention to detail. Viewed by some as the catalyst for a new wave of primetime period centric dramas (Boardwalk Empire, for example) the show has become for many the definitive media representation for this industry during this particular period.

And that my friends is the problem. Despite what is certainly an impressive dedication to detail, Mad Men is far from definitive. Like virtually all forms of historically based media, Mad Men possesses a number of inaccuracies and omissions that both shape the show’s narrative and define the manner in which it’s audience responds. Take for example the show’s portrayal of African Americans in advertising. In the 6 seasons Mad Men has been on the air there has been a grand total of ZERO black characters with roles actually responsible for creating ADVERTISING. No creative directors, no accountants, nothing. And while the general absence of black characters in the show has been discussed at length in a variety of forums (See the Root’s Black People Counter) it is a criticism that has often been written off by the shows creators as a fact of the times. When speaking about why there are so few black characters in Mad Men, show creator Matthew Weiner simply explained it as a fact of the time opining, “There are still no black people in advertising,”.

*Le Sigh*

If only Matthew Weiner and team paid as much attention to history as they did to wardrobe. George Olden, Roy Eaton and Caroline Robinson Jones not only represent three African American icons of Advertising, but also speak to a small but significant contingent of blacks in advertising during the 60s and beyond. Yes advertising has had well publicized issues with a lack of diversity, but to say that the 1960’s ad industry was devoid of any significant African American figures is not only inaccurate but revisionist in nature.

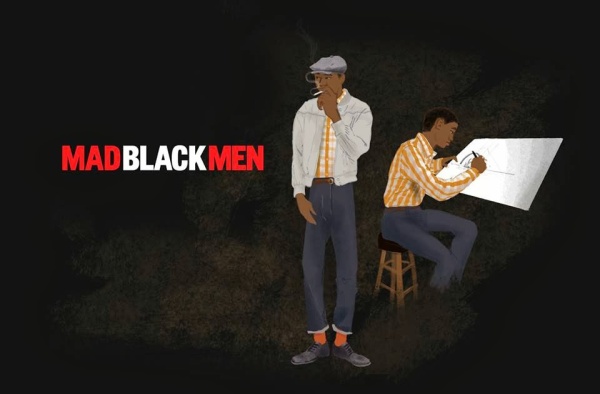

It is seemingly in direct response to the revisionist qualities of Mad Men that MAD Black Men was born.

A new project by writer and designer Xavier Ruffin, Mad Black Men is a satire that looks at the 1960’s AD industry through the eyes of black advertising agency employees. An independently funded endeavor , Ruffin looks to capture the a perspective that has been either overlooked or simply disregarded by the original Mad Men series. While it remains to be seen what the final product of Mad Black Men will look like, its presence highlights the important role that independent content can play in countering popular yet inaccurate media narratives.